Discover how ohmic heating revolutionizes food processing with uniform heating, energy efficiency, and improved food quality. Learn its applications and benefits for sustainable food production. It offers faster processing, better preservation of nutrients, and energy savings compared to traditional methods. Widely applied in blanching, drying, boiling, and pasteurization, ohmic heating supports sustainable food production and aligns with global goals for food quality and environmental care.

- Introduction

- Heating

- Heating, but differently

- Mechanism of Ohmic Heating

- Important Process Parameters

- Industrial Applications

- Advantages and Disadvantages of OH

- Advancements in Ohmic Heating: Exploring Non-Thermal Effects

- Future work

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Ohmic Heating shows strong promise for use in the food industry. It offers an effective alternative to traditional processing techniques and can be applied in various areas. Today, ohmic heating is widely used for:

- Roasting,

- Drying,

- Boiling,

- Cooking,

- Preheating,

- Extraction,

- Blanching,

- Fermentation,

- Peeling,

- Gelatinization,

- Pasteurization and sterilization,

- Microbial inactivation,

- and thawing (Javed et al., 2025).

This technology has been used across a wide range of foods, including vegetables, juices, soups, seafood, meat, creams, pasta, and ready-to-eat meals. It’s particularly useful for sterilizing products in glass containers, reducing acidity in tomato-based foods, and producing high-quality, low-acid items. It might sound surprising, but even the baking industry has explored its application—specifically investigating the potential of ohmic heating for gluten-free baking. Their findings revealed that this method enhanced the chemical and functional properties of gluten-free bread, leading to improved size, texture, elasticity, porosity, color, and starch gelatinization. Specific volume, elasticity, and porosity were notably better compared to traditionally baked gluten-free bread (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Its rapid and uniform heat distribution helps preserve essential qualities such as natural color, pH, taste, nutritional value, and bioactive components more effectively than traditional thermal methods (Javed et al., 2025).

Extensive studies have investigated the use of ohmic heating comparing it to conventional methods. Results suggest improvements in food safety, quality, and flavor, along with extended shelf life. Due to its ability to rapidly heat without excessively heating the food surface, ohmic heating is considered a promising alternative to conventional heat treatments and allows processing at lower temperatures (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Multiple studies have shown that ohmic heating is effective in various food manufacturing processes, with minimal impact on the nutritional, functional, structural, and sensory qualities of food when compared to conventional methods. It also contributes to enhanced food quality and effective enzyme inactivation. Ohmic heating is especially suitable for heating liquid foods, such as citrus juice (Alkanan et al., 2021).

This post presents information that underscores the versatility and effectiveness of ohmic heating in food processing. It enables rapid, uniform heating while preserving nutritional and sensory properties. Applications range from juices and vegetables to dairy and bakery products and others.

Ohmic heating has emerged over the past two decades as a highly effective method for food processing. Its adoption in the food industry has grown rapidly due to its numerous advantages. This post on FFFoodScience.com delves into the working principles of ohmic heating, its applications across different food processing sectors, and its impact on the nutritional and sensory properties of foods.

Several alternative technologies have been explored to replace conventional heating methods in food processing. Among these, ohmic heating—where an alternating current is passed through the food. Ohmic Heating has shown promising results, offering comparable performance along with notable benefits. It operates more quickly and uses less energy than traditional methods. Key advantages include uniform heating, reduced processing time, lower energy consumption, and enhanced product quality and safety. Studies have found that ohmic heating can use 4.6 to 5.3 times less energy than conventional heating (Alkanan et al., 2021).

The following points highlight how ohmic heating contributes to the achievement of various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs):

- Ohmic heating plays a key role in advancing several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by improving food systems, health outcomes, and environmental sustainability.

- It enhances food production and resource efficiency by increasing yield and extending shelf life.

- Ohmic heating supports SDGs 2 and 3 by contributing to healthier foods and improved nutritional quality.

- The technology also helps address SDGs 7, 12, and 13 by reducing energy consumption, minimizing waste, and lowering carbon emissions (Gavahian et al., 2025).

However, just like every new technology, there is a lot of research that needs to be done. Future research in ohmic heating is expected to focus on areas such as process modeling and prediction, analysis of food properties, in-depth characterization of treated products, and understanding the heating behavior of complex food systems. These studies are essential for optimizing the design of ohmic-based processes and for supporting the successful commercialization of products developed using this technology. With increasing interest in this emerging technology, it is important to highlight recent research on the potential industrial applications of ohmic heating in the food sector.

Just like in the rest of the posts in FFFoodScience.com, please use the table of content for easier navigation.

Heating

The primary goals of heat processing in foods are to ensure microbiological safety, and extend shelf life by deactivating harmful toxins, enzymes, and spoilage microorganisms as well as to enhance flavor in certain cases. While conventional heating methods are effective for ensuring microbial safety, they often fall short in preserving flavor, aroma, texture, and appearance and are also energy intensive.

To ensure the microbial safety, nutritional value, and sensory quality of food, it is essential to achieve effective inactivation of microorganisms and enzymes throughout the entire product (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024). Traditional techniques work by generating heat outside the food and transferring it inward through conduction, convection, or radiation. To ensure safety, the innermost part of the product—often called the coldest point—must reach a specific temperature. However, the time it takes to heat this central area can cause over-processing of the outer layers, leading to the loss of nutrients and deterioration of sensory qualities. This challenge is particularly evident when processing foods with large solid components (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Traditional thermal treatments often result in uneven heating, where some regions are over-processed to ensure that the coldest parts reach the required level of inactivation (Alkanan et al., 2021; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Traditional thermal techniques like pasteurization, sterilization, drying, blanching and evaporation are commonly used in the food industry to ensure microbial safety as well as inhibition of spoilage reactions (e.g. enzymatic reactions). However, these methods often lead to significant loss of nutritional components, particularly heat-sensitive vitamins and polyphenols. In addition, conventional treatments are relatively inefficient in terms of energy use, waste management, and environmental impact. With growing consumer demand for healthier foods that retain fresh characteristics and have longer shelf lives, researchers have been working on innovative approaches to enhance food quality and safety. Emerging alternatives to conventional heating generally allow shorter processing times, making them more energy-efficient, sustainable, and environmentally friendly. Among these, ohmic heating has gained recognition as one of the most cost-effective thermal processing technologies, relying solely on electricity for operation (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Heating, but differently

To address the limitations of conventional heat treatments, various non-thermal and innovative thermal technologies have been developed for food processing and preservation. These modern approaches aim to meet consumer expectations for high-quality, additive-free foods with extended shelf life. Their primary goal is to deactivate pathogens as well as other microorganisms and enzymes responsible for spoilage—while preserving the nutritional value and sensory qualities of the product.

Among these innovative technologies, ohmic heating has gained significant attention over the past two decades as a promising alternative. Also known as electroconductive or Joule heating, this method works by passing electric current directly through the food, converting electrical energy into heat internally (Misra, 2022).

Ohmic pasteurization offers a solution, especially for liquid and viscous foods, where electrical conductivity is more uniform. This method has been successfully applied to products such as fruit and vegetable juices, purees, and milk, offering more consistent heating than in solid foods (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Since many food materials contain ionic substances like water, acids and salts, they can conduct electricity, making them suitable for ohmic heating. This method generates heat directly within the material by converting electrical energy into thermal energy, allowing for rapid heating without the need for external heating surfaces or media. As a result, it helps preserve the quality of sensitive nutrients such as vitamins and pigments (Misra, 2022; Gavahian et al., 2025).

Unlike microwave or inductive heating, ohmic heating requires direct contact between the food and electrodes. Today, ohmic heating is being applied in the processing of various food products including juices, vegetables, and meats (Misra, 2022). This method is known for maintaining higher nutrient levels and causing minimal alterations to the sensory qualities of food (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Mechanism of Ohmic Heating

Thermal Effect

Ohmic heating works by generating heat within the food itself through Joule heating, as an electric current passes directly through the electrically conductive material. This internal energy production causes the temperature of the food to rise (Alkanan et al., 2021). Ohmic heating is a volumetric technique (Gavahian et al., 2025).

The heat inside the food is generated instantaneously and volumetrically as a result of the movement of ions. In other words, volumetric heating happens internally and uniformly, as the electric current flows through the food’s mass. Unlike conventional heating methods (like ovens or frying), where heat transfers from the outside and moving to inside towards the center (often unevenly), ohmic heating generates heat directly within the food’s interior due to the movement of ions and resulting resistance. So, “volumetric” in ohmic heating emphasizes that the entire bulk of the food heats up at once — not just the surface.

For ohmic heating, the material must be electrically conductive (at the end of this post there is a detailed explanation). Most foods contain significant amounts of water and dissolved salts, which helps in electrical conductivity. Electrical conduction heating, also known as ohmic or electrical resistance heating, works by passing an alternating electric current through food. This causes ions within the food to move toward electrodes of opposite charge, leading to collisions between ions. These collisions create resistance to ion movement, increasing kinetic energy and generating heat. The food is heated internally and uniformly as a result of this ionic movement. The amount of heat produced depends on factors such as the current, voltage, electric field strength, and the food’s electrical conductivity.

In certain cases, non-conductive materials can be made conductive by adding electrolytes like sodium chloride or certain organic salts, which do not interfere with the process, or by using ionic solvents, which are naturally conductive (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Non-Thermal (Electrical) Effect

While the primary mechanism of ohmic heating (OH) is thermal, some research suggests that there may also be non-thermal effects associated with the electric current. These effects could contribute to enhanced cell membrane permeabilization and increase the inactivation of microbes and enzymes by causing sublethal or additional structural damage (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Microbial inactivation by heat occurs through the disruption of various cellular structures, including the outer and inner membranes, the peptidoglycan cell wall, the nucleoid, RNA, ribosomes, and multiple enzymes. Damage to these components prevents the cells from reproducing, ultimately leading to their death. In contrast, exposure to high electric fields disrupts the selective permeability of cell membranes, disturbing cellular homeostasis and potentially resulting in cell death. In addition, the electrical (non-thermal) effects contribute to enzyme deactivation.

For more technical details and the parameters that affect ohmic heating, read the following chapter. Otherwise, skip this chapter and move to the next which is Industrial Applications.

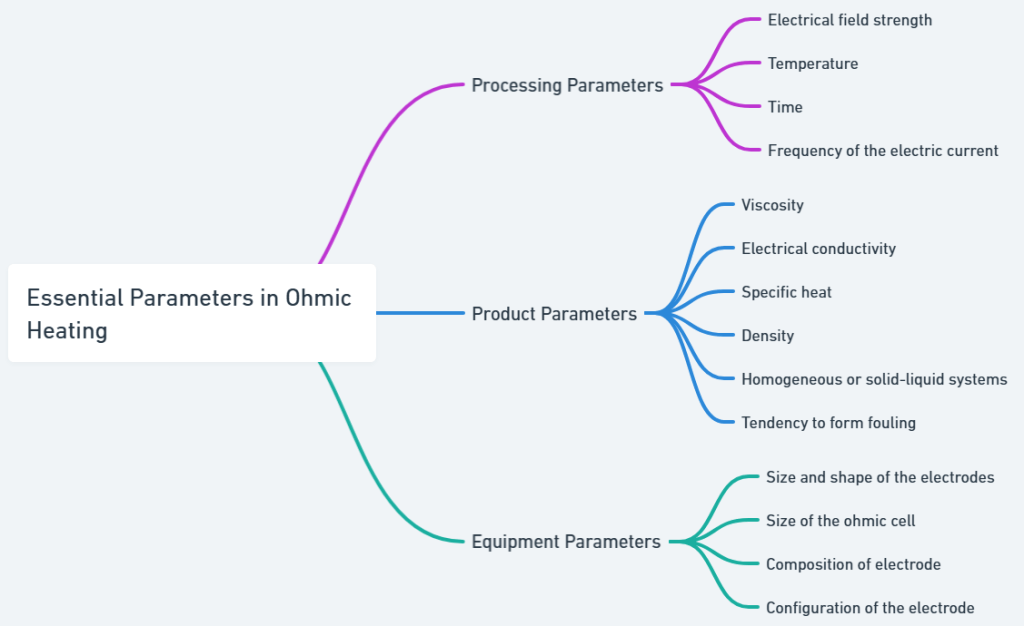

Important Process Parameters

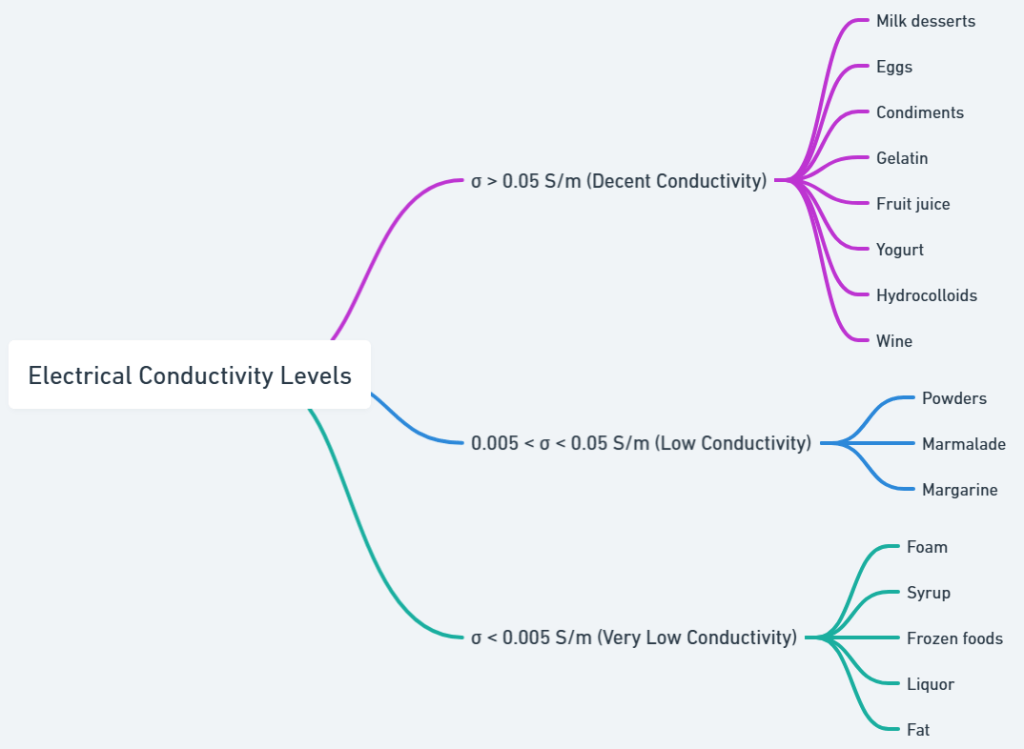

Electrical conductivity

In ohmic heating, electrical conductivity is a key factor influencing the rate at which a product heats up. It refers to a material’s capacity to conduct electric current through a given area over a specific time, under a unit potential difference.

Biological materials are generally considered poor conductors of electricity. They are broadly classified according to their electrical conductivity, as follows:

- σ > 0.05 S/m: These materials exhibit relatively good conductivity. Examples include milk-based desserts, eggs, condiments, gelatin, fruit juices, yogurt, hydrocolloids, wine, and similar items.

- 0.005 < σ < 0.05 S/m: These materials have low conductivity and require a higher electric field for processing. Examples include powders, marmalade, margarine, etc.

- σ < 0.005 S/m: These materials have very low conductivity, needing extremely high electric field strengths. They also pose challenges during ohmic heating. Examples include foams, syrups, frozen foods, liquor, fats, and related substances.

Food products with electrical conductivity in the range of 0.1–10 S/m are typically suitable for ohmic heating. The electrical conductivity of these products varies depending on factors such as voltage gradient, water content, frequency, and temperature. In ohmic heating, the rise in temperature occurs due to the interaction of ionic components and insulating elements within the complex structure of the food matrix (Misra, 2022; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025).

For food to be effectively heated using ohmic heating, it must possess a certain level of electrical conductivity to enable current flow. This conductivity is influenced by factors such as temperature, frequency, and the specific makeup of the food. In solid foods made up of multiple components, conductivity tends to vary throughout the product. As a result, various pre-treatment methods—like blanching, soaking, marinating, or vacuum infusion with salt solutions—have been explored to adjust and standardize conductivity across the entire food item.

Differences in conductivity within the food lead to uneven heating, creating zones of higher and lower temperatures, commonly referred to as hot and cold spots. The electric current naturally favors paths with less resistance—areas with higher conductivity—causing them to heat more rapidly (hot spots). In contrast, regions with lower conductivity heat less efficiently, forming cold spots. These cooler areas become critical when assessing the effectiveness of microbial inactivation during ohmic heating, as insufficient heating may leave harmful organisms alive. This issue is particularly pronounced in fatty foods, which are poor conductors of electricity. Since ohmic heating cannot effectively heat these non-conductive areas, parts of the product may not reach the temperatures necessary for ensuring food safety. Similar limitations are encountered in extraction processes where uniform heating is essential.

Electrical conductivity is a temperature-sensitive property that varies across different food materials. It typically exhibits a linear relationship with temperature, generally increasing as the material’s temperature rises. In liquid foods, this increase tends to follow a linear pattern with rising temperature. However, solid foods behave differently. As they are heated, their cellular structure begins to break down, releasing ions from within the cells. This leads to a sudden spike in both conductivity and temperature.

For example, when heating potato samples, two distinct phases of conductivity increase were observed. From 20 to 60 °C, the rise in conductivity was gradual. Beyond 60 °C, the increase became much more rapid. This shift aligns with the progression of cellular disintegration, which accelerates significantly after reaching 60 °C. The disintegration index, which measures the extent of cell breakdown (with 1 indicating complete rupture), increased steeply in this temperature range, eventually reaching values between 0.85 and 0.90.

In this context, applying a combination of ohmic heating and pulsed electric fields (PEF) to vegetables at electric field strengths above 1000 V/cm can lead to early electroporation of the tissue—occurring before the thermal breakdown typically seen at temperatures above 60 °C. This early disruption of cell membranes can help create a more uniform conductivity throughout the product during the initial phase of heating, thereby enhancing both the evenness and speed of the overall heating process. The cell disintegration index reached 0.87 for the ohmic-PEF treatment, compared to 0.51 for conventional ohmic heating. This indicates that the electroporation effect was more pronounced with ohmic-PEF, leading to greater cellular disruption. As a result, more ionic compounds were released, which contributed to a higher electrical conductivity in the food treated with ohmic-PEF (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025).

Electrical Field Strength

The way the electric field is distributed within the product being treated plays a critical role, as it directly affects both the heating rate and the degree of electroporation. However, accurately determining this distribution becomes quite complex for heterogeneous products, making the use of numerical simulation tools essential. For example, one study modeled ohmic heating at 5 V/cm for three different food items—carrot, meat, and potato—placed in a 3% NaCl solution within the same treatment chamber. In this setup, the solution’s conductivity was significantly higher—ranging from 1.8 to 15 times greater than that of the solid samples. The highest electric field intensity was found inside the carrot and potato, which had higher conductivity than the meat. Meanwhile, the regions between the solid pieces showed the lowest field strength. Similar results have been observed in other studies. Nonetheless, further research is needed, particularly on more complex food systems made up of multiple components with varying electrical and thermal properties, rather than just simple, uniform solids (Misra, 2022; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025).

Frequency and Waveform

Typically, a frequency range of 50–60 Hz is used for ohmic heating of food materials. Both the waveform and the frequency of the applied voltage influence the electrical conductivity of the sample as well as the efficiency of the heating process.

One key benefit of using higher frequencies is improved uniformity in heating—a topic that has gained growing interest. For instance, when potato tubers were treated at 300 kHz in a salt solution with a conductivity of 5 mS/cm, the temperature difference between the core and the outer edges was only 1.5 °C. In contrast, at a lower frequency of 12 kHz, the temperature gradient increased significantly to 7.1 °C (Misra, 2022; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025).

As previously mentioned, ohmic heating typically operates at frequencies between 50 and 60 Hz. However, recent research has explored the use of frequencies in the kilohertz range. It has been found that higher frequencies help minimize the electrochemical reactions at the electrodes, which are more common when using low-frequency or direct current systems. For this reason, frequencies between 12 and 300 kHz have been tested in more recent studies.

Product Size, Orientation, Viscosity, Ion and Particle Concentration, and Heat Capacity

In emulsions or colloids, where particles are generally smaller than 5 mm, the orientation relative to the electrical field has minimal impact on electrical conductivity. However, for larger particulates (15–25 mm), orientation significantly influences both electrical properties and the rate of heating. As particle size increases, electrical conductivity tends to decrease, which in turn lowers the heating rate. When solid particles are suspended in a liquid medium with similar conductivity, areas with lower heat capacity tend to heat more quickly. Foods with higher density and specific heat capacity generally undergo slower heating. It has been observed that increasing the concentration of strawberry pulp leads to a reduction in its electrical conductivity. Similarly, a higher solid concentration in carrot cubes results in longer heating times during ohmic processing.

Heating of biological materials leads to increased ionic mobility, which is a result of structural changes at the cellular level—such as cell wall breakdown, tissue softening, and reduced viscosity in the aqueous phase. These changes contribute to a rise in electrical conductivity. Additionally, an increase in ionic concentration promotes a faster heating rate (Misra, 2022; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025).

Industrial Applications

In the last 20 years, the use of ohmic heating in the food industry has expanded significantly, driven by efforts to overcome challenges like electrode fouling and polarization (Misra, 2022).

Ohmic heating allows for rapid processing of many liquid and liquid-solid food products. This method ensures uniform heating without creating large temperature differences within the food, helping to prevent surface overheating and preserve sensory qualities. Compared to traditional thermal techniques, ohmic heating uses less energy and requires shorter heating times. In some cases, products treated with ohmic heating have demonstrated shelf lives equal to or longer than those treated conventionally (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Ohmic heating (OH) can be applied through various methods depending on the type of food. For solid foods, it can be conducted either by placing electrodes in direct contact with the product or by submerging the food in a saline solution during a static process. For liquid foods, ohmic heating is typically applied through direct contact, either in batch mode or continuous flow systems.

Batch systems generally offer a more uniform electric field distribution. These setups usually involve chambers made of insulating materials, equipped with two parallel electrodes—often made from stainless steel, platinum, or titanium—positioned at opposite ends. Some batch chambers are designed to be pressurized, allowing them to handle sterilization treatments (Misra, 2022)..

On an industrial scale, tubular ohmic heaters are commercially available for the continuous processing of liquids or mixtures containing both liquids and particulates. These systems can feature a variety of chamber configurations tailored to different processing needs (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

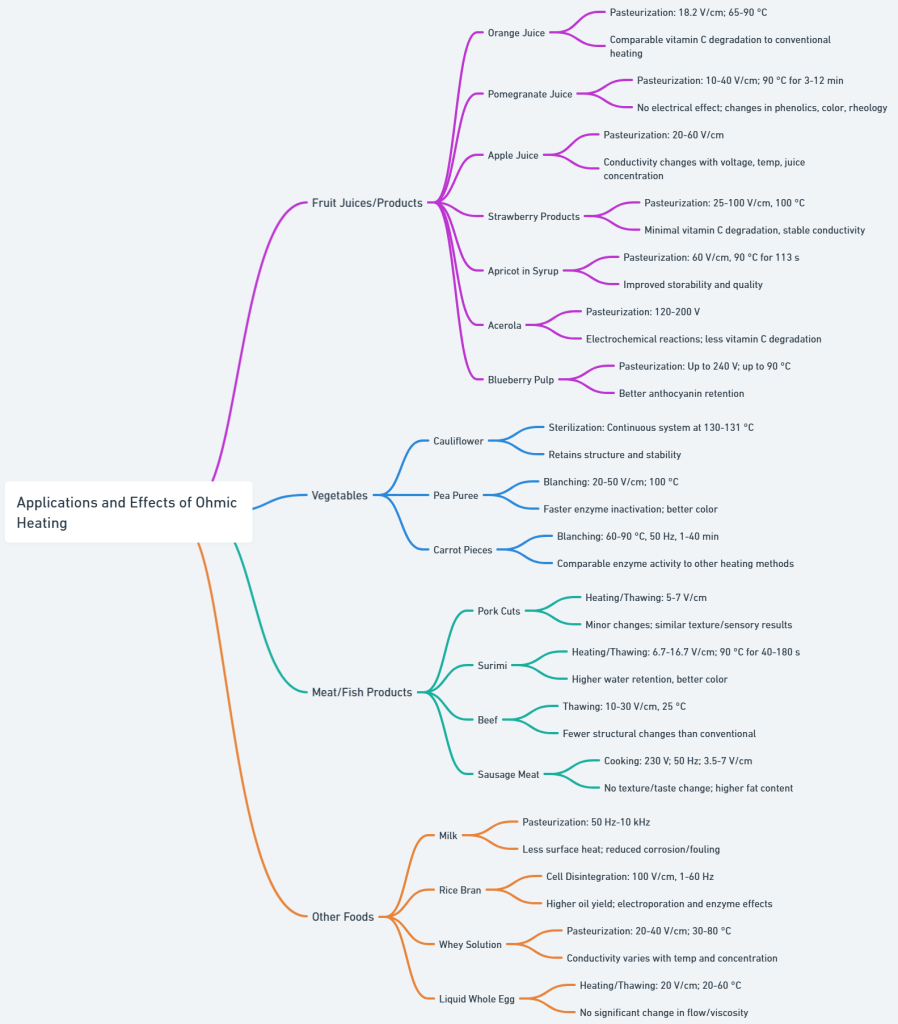

The diagram below lists some of the most recent industrial applications of OH. Click on the image to enlarge for easier reading.

Ohmic heating has been extensively investigated in various thermal food processes focusing on pasteurization and enzymatic inactivation of liquid products, extraction of compound from vegetables and fruits, peeling, cooking of meats, concentration of fruit juices, blanching and thawing of fish (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Blanching

Blanching plays a crucial role in food processing, serving multiple purposes such as preventing enzymatic or microbial spoilage, improving rehydration, removing internal gases, correcting undesirable flavors or cloudiness, and reducing sugar content. Traditional blanching methods using water or steam are resource-intensive, requiring significant amounts of water, time, and energy. These methods can also lead to the loss of soluble solids, which must be managed in wastewater treatment (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Fresh fruits and vegetables tend to spoil quickly after being harvested unless they are properly handled. To preserve their flavor, shelf life, and nutritional value, it is essential to process them into more stable forms. Blanching is a common pre-treatment method used before freezing, drying, or canning fruits and vegetables. Traditionally, this process uses hot water or steam, which can be slow and energy-intensive. As an alternative, ohmic heating offers a more efficient solution by using electric currents to rapidly raise the temperature, reducing blanching time.

Unlike conventional methods, ohmic blanching can be done without cutting the vegetables into smaller pieces. This maintains a lower surface-to-volume ratio, which helps minimize the loss of nutrients and other solutes during the process.

However, the application of an electric field can increase the extent of moisture loss from the product mixture. This effect can be advantageous in osmotic dehydration processes, as it helps in producing products with a higher dry matter content.

Improvements were observed in pea purée when blanching with ohmic heating, where ohmic blanching at higher voltage gradients (up to 50 V/cm) led to rapid inactivation of enzymes like peroxidase within 54 seconds. The result is improved color in pea puree compared to conventional blanching methods (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025). Overall, Ohmic heating results in more even heat distribution and minimal changes in texture and color compared to traditional techniques (Javed et al., 2025). Ohmic heating offers an efficient solution for blanching vegetable purees, helping to better preserve color quality (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

In addition, its application has shown several advantages, including reduced deep-frying time for potato slices by 10–15% while enhancing color and texture, maintaining higher solid content in mushroom caps with shorter treatment durations and comparable weight/volume loss (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Moreover, a brief blanching period using ohmic heating helps preserve the solid structure of the particles during the process, unlike conventional blanching methods. The shorter blanching time helps preserve the structural integrity of food particles. In complex mixtures like chicken chow mein, the sauce was more conductive than the solid pieces, which allowed for more uniform heating without negatively affecting the product’s taste or appearance.

Overall, findings suggest that ohmic blanching is advantageous in terms of speed, quality retention, and energy efficiency. Despite its promise, further research is needed to confirm its effectiveness across a broader range of food products and to support its adoption in industrial processing (Javed et al., 2025).

Summary of Key Information:

- Promising for industrial use, but broader validation is still needed .

- Ohmic heating increases dehydration efficiency and reduces blanching time dramatically (e.g., 4 hours to 3 minutes for strawberries).

- It enables faster enzyme inactivation.

- Provides uniform heat distribution with minimal texture and color changes.

- Maintains food structure better than traditional methods.

- Effective in both solid and mixed food systems without compromising sensory qualities

Food Preservation – Pasteurisation/Sterilization (Microbial and Enzymatic Inactivation)

Ohmic heating has been shown to be effective in pasteurizing juices, with its efficiency influenced by external factors like electric field strength and frequency, as well as internal factors such as pH and sugar content (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Pasteurisation is a heat-based method used to deactivate natural enzymes and eliminate microorganisms (either spoilage or pathogenic) in food. This process helps prevent the growth of harmful bacteria and enables the product to be packaged and stored. Traditionally, pasteurisation is carried out using heat exchangers that transfer heat through hot water or steam, with the effectiveness largely depending on the design of the equipment. These traditional methods often result in unwanted changes to food’s flavor, texture, and nutrient content (Alkanan et al., 2021; Javed et al., 2025).

As a response, newer thermal technologies like ohmic heating have emerged as promising solutions that can effectively inactivate microorganisms while preserving food quality. Ohmic heating offers more efficient and consistent heat distribution, reducing the risk of overprocessing (e.g. exposing the product to higher temperatures than required). As a result, this approach is increasingly being adopted in industrial applications (Alkanan et al., 2021; Javed et al., 2025).

Studies have shown that ohmic heating reduces nutrient loss—such as xanthophyll and carotene—in citrus juices like grapefruit and blood orange. Additionally, this method has minimal impact on sensory qualities of the juices. For example, flavor retention has been observed in orange juice treated with continuous UHT ohmic heating, which laso significantly improved its shelf life compared to conventional pasteurization (Misra, 2022; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Ohmic heating has gained significant attention for its superior thermal efficiency and is now widely adopted in the food industry for processing both liquids and solid-liquid mixtures (Misra, 2022; Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Ohmic heating is particularly effective for pasteurizing and sterilizing food products, especially those with large particles that are difficult to treat using conventional methods. It allows for ultra-high temperature (UHT) processing while maintaining efficiency.

Ohmic heating is increasingly being applied for the pasteurisation of a variety of food products, including dairy and fruit juices (Javed et al., 2025).

Role of Fat in Dairy Product Pasteurisation

Ohmic Heating uses electrical conductivity to generate heat within the product itself, resulting in more efficient and uniform thermal processing compared to traditional methods. However, in dairy products, the fat content significantly influences electrical conductivity, which directly affects the heating rate during ohmic pasteurisation. Lower fat content enhances conductivity and speeds up heating, whereas higher fat levels act as insulators, creating uneven heat distribution. These cold spots around fat globules reduce the effectiveness of microbial inactivation, potentially compromising microbiological safety. Despite this challenge, ohmic pasteurisation is particularly effective for lactose-free milk due to its naturally higher conductivity.

A major concern in thermal processing—especially with dairy—is fouling, which can hinder heat transfer, lower microbial stability, and necessitate frequent cleaning of equipment. If neglected, fouling can disrupt the uniformity of the electric field and encourage microbial buildup on surfaces. However, the extent of fouling in ohmic heating systems tends to be less severe than in conventional pasteurisation (Javed et al., 2025).

In dairy products, ohmic pasteurization has shown mixed outcomes. Some studies report improved sensory acceptance, such as better flavor and texture when using mild electric fields. Conversely, others observed negative effects on visual appearance and stability of bioactive compounds (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Ohmic Pasteurisation of Fruit Juices

Ohmic heating has shown promising results in processing fruit juices such as orange, apple, tomato, and fermented red pepper juice. For example, in orange juice, this method effectively deactivates heat-resistant enzymes like pectin esterase, which is linked to the degradation of sensory qualities. Compared to traditional techniques, ohmic pasteurisation shortens processing time, retains more flavor compounds, and significantly extends shelf life—often doubling it.

Other applications include coconut water, where ohmic pasteurisation successfully inactivates spoilage enzymes without causing undesirable color changes during storage—a problem often observed with traditional heating methods (Javed et al., 2025). Specifically, conventional pasteurization, causes a pink discoloration, ohmic pasteurization was able to prevent this defect, likely due to the electric field’s effect on polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Similar positive results have been noted in juices made from pomelo, apple, and other fruits, where nutritional and sensory qualities are better preserved (Javed et al., 2025).

Effects of Ohmic Heating on Microorganism Inactivation in Food

The impact of electric fields on microorganisms can vary depending on the size and type of the cells. Studies have compared microbial reduction using different frequencies of ohmic heating to conventional methods. In some cases, no significant difference in inactivation levels was observed between kilohertz-frequency ohmic heating and traditional thermal processes. However, other findings support that ohmic heating can still offer advantages due to simultaneous thermal and electrical effects.

The microbial inactivation observed during ohmic heating is primarily attributed to the heat generated during treatment. However, non-thermal mechanisms also contribute, including chemical and mechanical actions. Chemically, the formation of reactive species such as free radicals, oxygen, hydrogen, hydroxyl groups, and ionized minerals can damage microbial cells. Mechanically, the electric field can disrupt cell membranes, a phenomenon known as electroporation, which results in leakage of cell contents and eventual cell death.

Ohmic heating has shown particular effectiveness against heat-resistant spores like those of Bacillus subtilis. When applied under specific conditions—such as in saline solutions at boiling temperatures and with varying electric field intensities and frequencies—the method demonstrated superior inactivation compared to conventional heating. The results showed that higher field strengths and frequencies led to greater microbial destruction. For example, nearly complete inactivation of B. subtilis was achieved at higher frequencies and longer treatment durations, while lower frequencies were less effective over the same time period.

Experiments with juices, such as apple juice, have demonstrated the effectiveness of ohmic heating in eliminating pathogens like Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella Typhimurium, and Listeria monocytogenes. The performance of the ohmic system depended on the sugar content (measured in °Bx) and the applied voltage gradient. Lower sugar concentrations generally allowed faster heating, while higher sugar levels reduced heating efficiency. Specific combinations of sugar concentration and voltage gradient achieved significant reductions (up to 5-log) in pathogen counts within seconds, all without compromising the quality of the juice (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Efficiency and Energy Savings with Ohmic Heating

One of the key advantages of ohmic pasteurization is its ability to significantly reduce both processing time and energy consumption. This is achieved through rapid, volumetric heating. Several studies have demonstrated impressive energy savings and heating rates (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

This efficiency is largely due to the direct flow of electric current through the food, which converts electrical energy into heat internally with minimal loss—often exceeding 90% efficiency. In contrast, conventional heating methods such as convection, conduction, and radiation tend to be less efficient, primarily because of slower heating rates and heat loss to the surrounding environment. These inefficiencies arise from the reliance on external heat transfer, where energy must pass through temperature gradients or heated surfaces before reaching the food (Javed et al., 2025).

For instance, applying ohmic heating to guava pulp at various temperatures led to a 93% reduction in energy use and a 2.6 times faster heating rate compared to conventional methods. Similar energy reductions have been noted in the treatment of sheep’s milk, carrot puree, and dairy desserts.

When higher electric fields are used—as in moderate electric field (MEF) or ohmic-PEF technologies—these benefits are further enhanced. In one case, ohmic-PEF reduced pasteurization times by over 80%, showcasing its potential for highly efficient processing (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

A study showed that energy consumption was substantially lower with ohmic heating, requiring only 3.33–3.82 MJ per kilogram of water removed, as opposed to 17.50 MJ/kg with conventional methods—indicating a reduction in energy use by a factor of 4.6 to 5.3 (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Effect of Ohmic Heating on Bioactive Compounds in Food

Ohmic heating is a thermal processing method that better preserves bioactive compounds compared to traditional techniques like boiling or pasteurization. These compounds are crucial for nutrition and health, but they can degrade at high temperatures. Therefore, it’s important to find the highest temperature that still maintains their stability.

Studies on tomato juice show that ohmic heating preserves key bioactives like carotenoids (β-carotene, lycopene), phenolic compounds, and ascorbic acid at temperatures up to 110 °C. Lycopene remains stable even at varying temperatures and pH levels, and ascorbic acid is retained at 90 °C. Additionally, naringenin content increased after treatment.

The frequency of the electric field also plays a role. Low frequencies may cause ascorbic acid degradation and color changes, while higher frequencies minimize these effects. In tomato pulp powder production, ohmic heating helped preserve water-soluble compounds and enhanced lycopene’s antioxidant properties, supporting its role in maintaining both nutritional quality and appearance (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Effect of Ohmic Heating on Enzyme Inactivation in Food

Ohmic heating offers precise control and has shown promise in inactivating enzymes while preserving food quality (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Enzymes are essential in food processing, offering benefits such as flavor enhancement, by-product recovery, and improved extraction efficiency. However, they can also negatively affect food quality by generating unpleasant odors, altering taste, and changing texture. Therefore, controlling enzyme activity is a crucial step in various food processing stages to ensure the desired quality and functionality of the final product.

Extensive research has been conducted to understand the behavior of enzymes under electric field exposure, particularly focusing on inactivation kinetics. Ohmic heating has demonstrated superior performance in deactivating a wide range of enzymes found in fruits and vegetables (Javed et al., 2025).

Electric and thermal energy can disrupt the 3D structure of enzymes, impacting their function. Studies show that ohmic heating effectively reduces enzyme activity more efficiently than conventional methods. For example, in sugarcane juice, polyphenol oxidase activity dropped by nearly 98% at 60–90 °C with increasing electric fields. Similarly, in water chestnut juice, ohmic heating both activated and then rapidly inhibited peroxidase, with stronger effects observed at higher electrical conductivity.

In tomato juice, ohmic heating at 90 °C for 1 minute successfully inactivated pectin methyl esterase and polygalacturonase—faster than traditional heating, which required 5 minutes. It also proved effective in reducing urease activity in soymilk and inhibiting multiple enzymes like polyphenoloxidase, lipoxygenase, and alkaline phosphatase across different food matrices.

Additionally, ohmic heating altered enzyme kinetics without changing the fundamental inhibition mechanisms. Peroxidase showed the most sensitivity, especially in carrot juice, while other enzymes like pectin methyl esterase and alkaline phosphatase remained more stable. pH also influenced enzyme response, with greater inhibition seen at higher pH levels for some enzymes like polygalacturonase (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Considerations for Industrial Application: While ohmic heating shows promising potential for enzyme inactivation, especially for enzymes like polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and pectinmethylesterase (PME) in products such as mango juice, certain challenges remain. Electrochemical reactions that may occur during processing still need to be thoroughly addressed and controlled before widespread industrial-scale implementation can be realized (Javed et al., 2025).

Challenges in Comparison and Standardization

Comparing results across different studies is difficult due to variations in treatment conditions. Differences in processing mode (batch vs. continuous), food type, and the lack of standardized lethality measurements complicate direct comparisons. Moreover, detailed information about ohmic parameters is often missing, making it harder to evaluate or replicate outcomes (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

A Promising but Context-Dependent Technology

Ohmic heating offers a promising alternative for industrial-scale pasteurization, with benefits including improved microbiological stability, nutritional retention, and shorter processing times. However, challenges such as cold spot formation and fouling, especially in high-fat dairy products, remain areas requiring further study to optimize performance and ensure consistent product quality (Javed et al., 2025).

Ohmic pasteurization shows strong potential for reducing processing times and preserving food quality. By shortening thermal exposure, it often leads to improved sensory and nutritional outcomes. However, the impact of electric fields on bioactive compounds can vary depending on the food type, requiring careful optimization. For best results, the technology must be tailored to the specific properties of each product (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Extraction

Ohmic heating is being explored as a green technology to extract valuable compounds from fruits and vegetables (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024). By applying an electric field during ohmic heating, cell-membrane permeability is enhanced, and as temperature increases, diffusion of intracellular substances becomes more efficient. This method has demonstrated the potential to achieve higher extraction yields compared to traditional techniques, which often depend on substantial amounts of organic solvents and require lengthy processing times (Javed et al., 2025).

Numerous by-products from the food industry—such as peels, seeds, and fermentation residues—contain valuable substances like phenolic compounds, dietary fiber, hydrocolloids, pectins, organic acids, and carotenoids, which can be used as natural additives. Ohmic heating minimizes the need for harmful solvents and promotes more sustainable processing. It has shown promise in recovering pectins from citrus peels, anthocyanins from grape skins, polyphenols from tomato by-products, betalains from beetroot, and phytochemicals from Stevia leaves (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

For example, a rapid ohmic heating treatment of grape peel—from 40 °C to 100 °C in 20 seconds—increased anthocyanin content by 20% compared to conventional methods, while minimizing heat damage (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024). Factors such as voltage, frequency, and solvent choice significantly affect efficiency: acidified ethanol–water improved betalain extraction from beetroot at lower voltages, though its benefit diminished at higher voltages and frequencies (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Traditional methods typically operate at 50–60 °C for 3 to 20 hours, risking degradation of heat-sensitive compounds such as polyphenols, flavonoids, antioxidants, and other bioactives. Ohmic heating, by contrast, uses lower energy and shorter times, protecting functional properties and yielding higher concentrations. For instance, pectin extraction from orange juice improved under higher voltage gradients, and oil extraction from rice bran showed a 75% reduction in processing time when using ohmic heating.

A variant of ohmic heating, called Pulsed Ohmic Heating, uses a pulsed waveform rather than a sinusoidal one, reducing electrode corrosion and metal-ion leaching (Cho & Kang, 2022). It combines electrical and thermal treatments at moderate conditions and has enhanced polyphenol extraction from red grape pomace, sucrose recovery from sugar beets, rice bran oil and bioactives extraction, beet dye isolation, and apple juice recovery (Misra, 2022).

Applications extend beyond fruits and vegetables. Ohmic heating has increased sucrose yields from sugar beets, beet roots, and soybeans, and improved oil extraction from tepurang fruit—achieving higher β-carotene and lycopene content, better color quality, and greater efficiency. It has also been effective in extracting inulin from Jerusalem artichoke bulbs, with product yields surpassing those of conventional methods.

Rice bran processing has benefited substantially: ohmic-treated bran can yield up to 82% of total lipids, and lower electric-field frequencies further enhance yield via electroporation of cell walls. In anthocyanin extraction from black rice bran, ohmic heating outperformed steam-assisted methods, producing higher yields of colorant powders.

Similarly, in citrus and berry by-products, uniform heat distribution and increased cell-wall permeability improve phenolic-compound recovery. Pectin from orange juice by-products exhibits superior viscosity and quality, and berry fruits like cornelian cherry yield higher phenolic content and better antioxidant preservation, thanks to shorter treatment times that protect anthocyanins and other sensitive compounds (Javed et al., 2025).

While ohmic heating offers an environmentally friendly alternative—reducing energy consumption, shortening processing times, and increasing both yield and quality—widespread industrial adoption still requires careful optimization of parameters such as electric field strength, frequency, solvent choice, and treatment duration to ensure consistent, scalable results (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025).

Dehydrarion (Drying Pre-Treatment)

Drying is essential for food preservation but is energy-intensive. Technologies that accelerate water removal, like ohmic heating (OH), are gaining attention for their efficiency.

Ohmic heating has been tested as a pre-treatment to speed up drying. In one study, applying ohmic heating to tomato paste (6–16 V/cm, up to 95 °C) reduced drying time by up to 87% compared to conventional air drying. Similarly, ohmic heating blanching before microwave drying of mushrooms showed no negative impact on drying rates.

A novel method used needle-shaped electrodes to apply ohmic heating directly inside potatoes. This setup cut drying time by 20–60%. However, as moisture decreased, ohmic heating efficiency dropped (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Ohmic heating (OH) has shown significant potential in enhancing mass transfer processes, particularly in reducing moisture content and improving food dehydration efficiency. Traditional thermal dehydration methods are often energy-intensive and time-consuming, making ohmic heating a promising pre-treatment strategy to accelerate these processes.

Grape drying was significantly improved when ohmic heating was applied at an electric field strength of 14 V/cm, with a temperature of 60 °C and frequency of 30 Hz. The treatment caused skin rupture in the berries, which facilitated moisture loss. Similarly, increasing the electric field strength and energy input during ohmic heating treatment led to higher moisture diffusivity and drying rates in potato tissue. In fact, ohmic heating reduced the required drying temperature for potatoes by approximately 20 °C, with visible tissue damage attributed to electroporation, which helped redistribute water within the vegetable and altered its sorption behavior.

Ohmic pre-treatment has also been effective in osmotic dehydration. For example, apple cubes treated with ohmic heating lost 25% more water over a 240-minute period than untreated samples. In strawberries, Ohmic heat-treated samples achieved 68% dry matter content compared to 20.3% in untreated ones, due to structural changes induced during the short ohmic heating exposure, which enhanced water removal during dehydration.

There are several examples reffering to combining ohmic heating with other processing methods like vacuum impregnation; has further improved dehydration outcomes.

Although ohmic heating shows promise, other non-contact electro-technologies like microwave and radiofrequency drying may offer better efficiency and are also under investigation (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Overall, the integration of ohmic heating as a pre-treatment in dehydration processes improves moisture removal, preserves bioactive compounds, and helps maintain the structural integrity and firmness of fruit products (Misra, 2022).

Concentration

Concentration is widely used in the juice industry to extend shelf life and reduce packaging, storage, and transport costs. Ohmic heating (OH) offers advantages in this process due to its rapid and uniform heating.

Ohmic heating has been shown to reduce fouling, lower cleaning costs, and preserve juice quality, as seen in sour cherry juice processing. It also shortens processing time and reduces energy use—studies report time reductions of 44% for apple juice and 68.5% for mulberry juice. Higher electric fields improve efficiency and enhance total polyphenol content and antioxidant activity.

However, as water evaporates, the juice’s conductivity increases up to boiling, then drops as moisture is lost, which can affect ohmic heating efficiency (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

In another study they used ohmic heating for milk concentration through evaporation. Traditional methods often cause aroma loss and undesirable color changes. Ohmic heating was applied to cow, buffalo, and mixed milk under 13.33 V/cm, current levels of 5–20 amps, and temperature up to 100 °C for 75 minutes. The process yielded improved microbial safety and food quality. Increases in free fatty acids, viscosity, and key color values (redness and yellowness) were observed. Although brightness (L*) and pH slightly declined, the final product showed enhanced shelf life and sensory appeal (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Finally, a research on black mulberry juice concentration demonstrated that ohmic heating resulted in significantly higher phenolic content—up to 3 to 4.5 times greater—compared to traditional heating. Additionally, the process maintained stable pH and total phenol levels even under higher voltage gradients (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Fermentation

Fermentation is a multifaceted biological process that relies on optimal physical conditions—such as pH, temperature, enzyme activity, microbial presence, and sufficient water availability—to function effectively. To support and enhance these conditions, ohmic heating has been explored as a method to regulate them more precisely during fermentation. This technique is primarily used to maintain ideal temperature levels and timing across all fermentation stages, with the goal of maximizing product yield and quality (Javed et al., 2025).

The electroporation effect caused by ohmic heating is thought to promote microbial activity at suitable temperatures, thereby speeding up the fermentation process (Javed et al., 2025).

Research has explored the effects of both conventional and ohmic-heated environments on fermentation, focusing on various microorganisms and food products. Findings show that ohmic heating significantly shortens the lag phase and overall fermentation time, likely due to enhanced nutrient transfer caused by electroporation. While this method boosts microbial activity in early fermentation stages, its use in later phases can reduce productivity and is therefore not recommended at that point.

In bread production, ohmic heating notably decreases dough proofing time by up to 50%, thanks to its faster heating rate, which allows yeast to quickly reach optimal temperatures. This method also proved suitable for fermenting gluten-free bread by supporting crumb structure formation and precise temperature control.

In the coffee industry, controlled fermentation using ohmic heating improves processing by reducing acidity and preserving flavor quality. Ohmically fermented coffee scored highly in sensory evaluations, qualifying as specialty coffee. Similarly, in cocoa processing, ohmic heating reduced fermentation time from 5–7 days to just 3 days, without sacrificing yield or quality. The rapid temperature regulation at the start of the process helps overcome microbial lag, although more research is needed to fully understand its broader effects (Javed et al., 2025).

Overall, while studies are limited, the use of ohmic heating in fermentation shows strong potential to enhance processing speed, control, and product quality across various industries (Javed et al., 2025). Ohmic heating can accelerate fermentation by quickly achieving and maintaining optimal temperatures and influencing substrates by releasing micronutrients, thereby affecting microbial activity.

One of the most studied applications involves the use of MEF and ohmic heating in fermentations involving Lactobacillus acidophilus. In low-intensity ohmic treatments (electric field ≤ 1.1 V/cm), the lag phase of fermentation at 30 °C was reduced significantly—up to 18 times faster compared to conventional heating. This improvement is likely due to electroporation, which enhances nutrient transport into the microbial cells. Ohmic heating has shown beneficial effects during the early stages of lactic acid fermentation; however, during later stages, it may reduce productivity due to the accumulation of inhibitory metabolites. For instance, the synthesis of bacteriocins like lacidin A was delayed and its activity reduced when ohmic heating was applied continuously, suggesting that ohmic heating is best suited for the initial stages of fermentation and should be avoided during the stationary phase.

Overall, ohmic heating offers several advantages in fermentation processes, particularly in the early stages, by enhancing temperature control, nutrient uptake, and process speed, while caution is needed during later phases to prevent negative impacts on product yield and quality.

Thawing

Ohmic heating is also used for thawing or defrosting frozen foods. This process is crucial for maintaining the microbiological safety of the product and should be done rapidly at low temperatures to preserve its physical and chemical qualities (Javed et al., 2025).

Thawing is a critical and time-sensitive step in food processing, as delays can impact both safety and quality (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024). Traditional thawing methods often take longer, which can promote microbial growth on the surface. Additionally, these methods may cause a loss of nutrients due to protein leaching, require more fresh water, and generate large amounts of contaminated wastewater. As a result, there is a growing need for faster and more efficient thawing methods in the food industry (Javed et al., 2025). Ohmic heating offers a fast and uniform alternative to conventional thawing methods (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Studies show ohmic heating can drastically cut thawing times—by 82% for spinach and 30% for tuna. This is achieved by immersing the food in a conductive solution or placing it in direct contact with electrodes. As ice melts, conductivity rises, enabling effective heating. Due to this, uniform heating is challenging due to the difference in conductivity between frozen and thawed regions. (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

As thawing begins, electrical conductivity increases significantly in the thawed sections compared to the still-frozen parts—up to 100 times in the case of shrimp (Misra, 2022; Javed et al., 2025). This uneven conductivity causes the current to concentrate in the thawed areas, potentially overheating and partially cooking them while other parts remain frozen. This phenomenon, known as “runaway heating” or the formation of “hot spots,” poses a limitation to uniform thawing. If this issue can be addressed, ohmic heating could become a highly effective method for thawing products like beef and other complex frozen items (Misra, 2022). This unevenness is a challenge that requires further process optimization (Javed et al., 2025).

In addition, research on tuna revealed that heating uniformity varies by muscle orientation and cut, with parallel current flow yielding the best results. Conductivity increases significantly as temperatures rise from −3 °C to 0 °C, where more water transitions to liquid. Fat content and product shape also influence ohmic heating performance. Direct electrode contact requires flat surfaces to avoid uneven heating, which is easier to achieve using plate freezers.

Overall, ohmic heating presents a promising, energy-efficient method for improving thawing speed and quality, though careful control and setup are essential (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

In ohmic heating-based thawing, frozen foods are placed between two electrodes and subjected to an alternating current. This technique offers several advantages, including the absence of water or wastewater generation, the potential for relatively uniform thawing, and ease of process control due to volumetric heating (Misra, 2022).

Other examples showed that, when applied to frozen vegetables like potato cubes, the process time was reduced by over 99%, resulting in a softer texture and minimal color changes. Similar benefits were observed in thawing frozen meat, where increasing the voltage gradient accelerated the process and improved the energy utilization ratio. These outcomes suggest that ohmic thawing can enhance both speed and energy efficiency while preserving product quality better than conventional methods (Javed et al., 2025). Ohmic thawing has also been explored in liquid food applications, such as sour cherry juice concentrate. In these cases, thawing times were reduced by nearly 90% (Javed et al., 2025).

While ohmic heating offers clear advantages in speed and efficiency, challenges related to uniform heat distribution remain, particularly for products with varying densities and shapes. These issues can lead to quality degradation if not properly managed. Therefore, further investigation is necessary to understand the full impact of ohmic thawing on food quality and to refine the process for consistent results across different food types (Javed et al., 2025).

Cooking

Cooking transforms food by softening texture, enhancing flavor, and improving digestibility. However, uneven or excessive heat can lead to quality loss or burnt surfaces. Ohmic heating (OH) offers a fast, uniform alternative that helps maintain food quality while reducing cooking time (Javed et al., 2025).

Numerous investigations have explored the potential uses of ohmic heating, demonstrating encouraging outcomes in reducing cooking time and maintaining color and sensory qualities. However, much of this research has been carried out in laboratory settings, and its practical application on an industrial scale has yet to be fully validated through real-world implementation. Nonetheless, ohmic cooking is a promising technique for industrial use and has yielded positive results when applied to solid food products (Javed et al., 2025).

Experiments comparing different heating methods have shown that ohmic heating can significantly improve cooking efficiency and product quality. When applied to vegetables like red beet, potatos and carrot, ohmic heating resulted in a softer texture and faster softening compared to conventional and microwave methods (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024; Javed et al., 2025). However, vegetable peels can act as electrical insulators, causing uneven heating unless properly managed. In rice, it accelerated grain expansion and reduced energy use by up to 75% compared to electric rice cookers (Javed et al., 2025). .

Ohmic heating has also been tested extensively on meat products. It consistently reduced cooking time—sometimes by up to tenfold—and produced more uniform and lighter color in turkey meat. Studies on ground beef and meatballs confirmed improvements in texture, sensory qualities, and microbial reduction, all contributing to better overall meat quality (Javed et al., 2025). In addition, in meat processing, ohmic heating has also shown potential to reduce cooking losses significantly—up to 41% in beef—while maintaining tenderness and color. This is linked to much faster heating, cutting cooking times by over 90%. However, results can vary by meat type and setup. For example, improvements weren’t observed in pork cooked with direct electrode contact, suggesting further research is needed to optimize parameters for different products (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

These findings highlight the strong potential of ohmic heating for cooking a wide range of food products. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to evaluate its impact on nutritional properties, especially in large-scale industrial applications (Javed et al., 2025).

A particularly promising application is ohmic baking of gluten-free bread. Due to the rapid, even heating, bread structure forms before CO₂ escapes, doubling crumb volume compared to conventional baking. While crust color may vary slightly, the crumb remains consistent.

Overall, ohmic heating is a practical, efficient cooking method that preserves sensory and nutritional quality. It’s already entering the consumer market, with home-use devices like the Sevvy cooker now available (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Peeling

Traditional peeling methods often use bleach (NaOH) to break down pectins in the plant cell wall by diffusion, which can be slow and chemical-intensive. Ohmic heating enhances this process by accelerating diffusion and reducing the amount of chemical needed.

In tomato peeling, ohmic heating significantly shortened peeling time, defined as the moment the peel starts cracking. Studies show that higher electric field strengths and greater NaOH concentrations both reduce peeling time. This is due to faster electroporation and heating, as well as improved solution conductivity.

Advanced techniques like moderate electric fields (MEF) and pulsed ohmic fields (ohmic-PEF) may further enhance peeling efficiency, making ohmic heating a promising technology for reducing chemical use and improving process speed (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Protein Gel Formation

Beyond thermal denaturation, ohmic heating (OH) can alter the secondary and tertiary structure of proteins due to the electric field applied during processing. These changes can lead to protein aggregates and gels with different characteristics compared to those formed through conventional heating.

OH-treated gels often show variations in texture, viscosity, water-holding capacity, solubility, and firmness. For instance, whey protein gels formed after ohmic heating treatment were more elastic, retained more water, and had lower solubility. OH-treated soymilk produced firmer, more resilient gels. However, applying ohmic heating during the gelation process sometimes results in weak, fluid-like gels with small aggregates and poor structure.

While the full impact of ohmic heating on protein gelation remains unclear, it presents opportunities for creating new textures and functionalities in food products. Further research is needed to better understand and control these effects (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Food Allergenicity

A key concern with novel food processing technologies is their impact on allergenicity, which directly affects consumer health. Major allergens—such as those in milk, soy, eggs, fish, and nuts—contain proteins that can be either heat-resistant or heat-sensitive. Since ohmic heating (OH) primarily relies on thermal energy and electric fields, it may influence the structure and immunoreactivity of these proteins.

Preliminary studies suggest that ohmic heating can reduce allergenicity in some cases. For example, ohmic heating has been shown to lower the immunoreactivity of β-lactoglobulin and soybean trypsin inhibitors under specific electric field and frequency conditions. In one study, ohmic heating achieved a 70% reduction in eel collagen allergenicity with much less time and energy than conventional heating. Similar results were found for parvalbumin in fish.

However, the effects vary widely depending on the type of allergen, processing parameters, and food matrix. While early findings are promising, more research is needed to fully understand and validate the potential of ohmic heating in reducing food allergenicity (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Wastewater Treatment with Ohmic Heating

Surimi production generates large volumes of wastewater with a high biological oxygen demand (BOD), making treatment essential. One effective method to reduce BOD involves heating the protein-rich wastewater, which causes protein coagulation. Ohmic heating has shown high efficiency in this process (Javed et al., 2025).

A continuous ohmic heating system was developed and tested at a pilot scale, achieving around 60% protein coagulation in surimi wastewater. Using higher electric field strengths and slower flow rates led to increased temperatures, enhancing the treatment efficiency. This method offers several benefits, including faster processing, lower chemical usage, and improved temperature control for optimal protein coagulation. However, additional research is needed to support its large-scale industrial implementation, as current studies remain limited (Javed et al., 2025).

Advantages and Disadvantages of OH

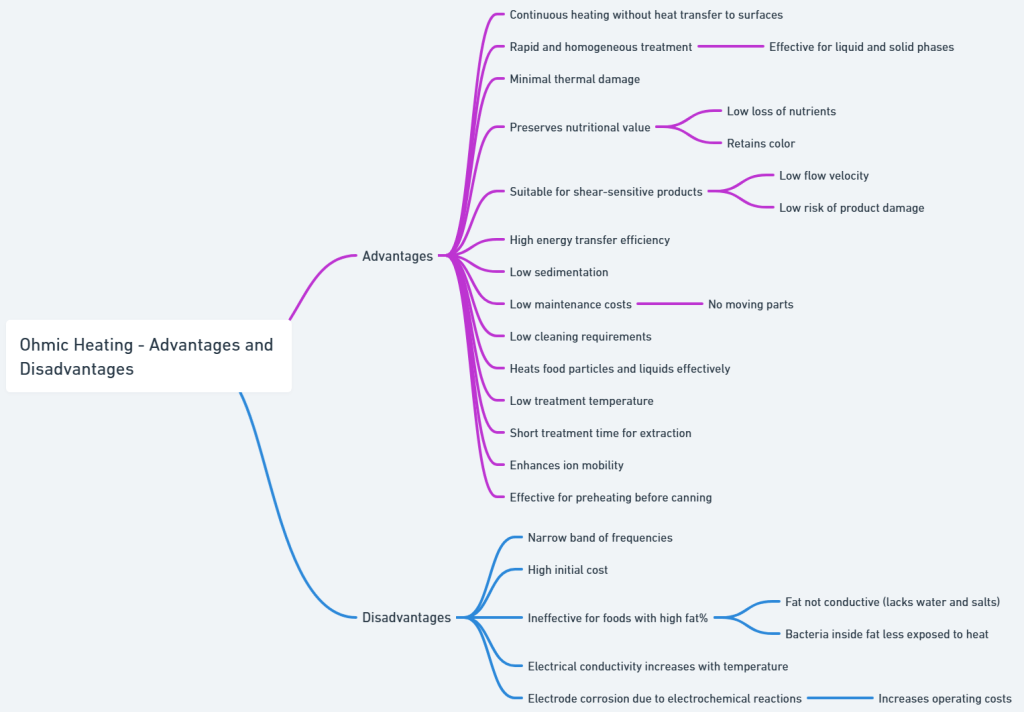

Advantages of Ohmic Heating

- Efficient and Uniform Heating

- Delivers rapid and consistent heating of both liquids and solids with minimal thermal damage and nutrient loss.

- Maintains food color and nutritional quality.

- Reduces the risk of scorching or burning the product.

- Energy and Process Efficiency

- Offers high electrical-to-thermal energy conversion efficiency.

- Enables continuous processing without heat-transfer surfaces.

- Results in lower maintenance costs and increased production efficiency.

- Product Handling and Compatibility

- Ideal for heating shear-sensitive materials due to low flow velocity.

- Capable of effectively heating liquid-particulate mixtures and solid-containing foods.

- Causes less fouling than conventional heating methods.

- Hygiene and Maintenance

- Requires less frequent cleaning.

- Lowers the likelihood of fouling and equipment buildup.

- Cost and Environmental Benefits

- Reduces capital costs by supporting high solid loadings.

- Operates as an environmentally friendly system (Misra, 2022).

- Achieves UHT (Ultra-High Temperature) Levels

- Can reach temperatures required for sterilization processes.

- Effective Pre-Heating Before Canning

- Suitable for rapid pre-heating of products prior to canning or other preservation steps.

- More Economical Than Microwave and Conventional Heating

- Lower operational and energy costs compared to alternative heating technologies.

- Supports Large-Scale Industrial Applications

- Can be implemented in heavy-duty ohmic cookers or batch ohmic heaters for large-volume processing

- Efficiently processes mixtures with a high ratio of solids to liquids

- Ohmic heating is gaining popularity for large-scale processing of thick, particle-rich foods like soups, sauces, stews, salsas, and heat-sensitive liquids such as milk, egg products, whey, soymilk, and ice cream mix (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Disadvantages of Ohmic Heating

- Technical and Operational Challenges

- Difficult to monitor and control due to complex interactions between temperature and electric field distribution.

- Limited frequency range restricts flexibility in processing.

- Risk of “runaway” heating as increased temperature boosts electrical conductivity, potentially leading to overheating.

- Material and Product Limitations

- Ineffective for heating foods with fat globules, since fat lacks water and salt, making it poor in conductivity.

- Effectiveness depends heavily on the electrical conductivity of the food, such as milk, which can vary.

- Maintenance and Equipment Issues

- Fouling during processing may lead to the buildup of deposits on electrodes, increasing the risk of corrosion.

- High installation and operating costs compared to traditional thermal methods.

- Information and Research Gaps

- Generalized data and standardized design information are currently lacking, making adoption more difficult (Misra, 2022).

- Limited to Direct Current (DC)

- Ohmic heating systems are typically restricted to DC, limiting flexibility in power supply and system design.

- Narrow Frequency Band (clarification needed)

- Though mentioned, the implications of a narrow usable frequency range (e.g., impact on heating control or food compatibility) could be expanded for clarity (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Advancements in Ohmic Heating: Exploring Non-Thermal Effects

While ohmic heating is primarily known for its thermal effect, it can also produce non-thermal effects—particularly at higher electric fields—such as enhanced inactivation of spores and enzymes. These effects are more noticeable in advanced systems like Moderate Electric Fields (MEF) and ohmic-Pulsed Electric Fields (ohmic-PEF), which apply stronger electric fields than conventional ohmic heating.

These systems offer dual benefits: faster heating and improved electroporation, especially in eukaryotic cells. This can increase the release of intracellular compounds, improve conductivity uniformity, and result in more even heating—especially important for processing large or complex solid foods where conventional methods often cause uneven temperature distribution.

To better understand and optimize these processes, numerical simulation tools are increasingly used to model heat flow based on factors like food composition, equipment design, and treatment conditions.

Despite their promise, more research is needed on MEF and ohmic-PEF technologies. Key areas include isolating electrical effects, improving heating uniformity, designing equipment for large-scale applications, and assessing impacts on food quality. Standardized methods are also essential to reliably compare these systems to traditional thermal processing (Astráin-Redín et al., 2024).

Future work

Ohmic heating is an innovative and promising technique for processing food and beverages, with significant potential for industrial use. Although current studies show that it can yield high-quality products, there is still limited understanding of its precise effects and mechanisms. For widespread adoption, comprehensive research is needed to evaluate both processing conditions and product characteristics. This will support the development of accurate simulation models for improved process control and system optimisation.

One of the major challenges lies in selecting suitable electrode materials and designs. Electrodes must be durable and compatible with specific operating conditions, as unwanted electrochemical reactions can lead to corrosion. These reactions are influenced by multiple factors, including the type of electrode, electrical field parameters, and the composition of the food, which itself varies widely and affects conductivity and heating efficiency.

Processing solid foods adds further complexity due to the uneven distribution of conductive materials, which can create temperature inconsistencies. To address this, simulations using numerical models and computational fluid dynamics can help predict heat distribution and support more uniform heating outcomes.

Additionally, the impact of different electric field intensities—such as those used in Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) and Moderate Electric Field (MEF) techniques—needs further investigation. Each may offer unique benefits depending on the food type. Future research should explore their effects on heating uniformity, efficiency, sensory qualities, nutritional value, and shelf life. Comparisons with traditional heating methods are essential to validate these approaches for real-world industrial applications (Javed et al., 2025).

Conclusion

Conventional heating methods in food processing, such as conduction and convection, rely on fossil fuels, resulting in high emissions and poor energy efficiency. These surface-based heating techniques are also time-consuming. In contrast, ohmic heating offers a more sustainable and efficient alternative, with promising applications in processing fruits, vegetables, meats, juices, and sauces. It enables faster processing, better energy use, and improved product quality while preserving nutritional and sensory properties.

However, the effectiveness of ohmic heating depends on factors like electrical conductivity, voltage, frequency, and electrode materials, which must be tailored to specific food types. Challenges remain, such as uneven heating in products with nonconductive components like fats, and the need for better temperature control. Most research so far has been limited to lab settings, and industrial-scale implementation is still limited due to high investment costs. Further research is needed to improve uniform heating and assess large-scale feasibility (Javed et al., 2025).

Ohmic heating is an energy-efficient method with promising applications in food processing and beyond. It can be used alone or combined with other techniques like infrared heating for improved sterilization and microbial reduction. Applications include aseptic packaging, protein preservation, probiotic delivery, essential oil extraction, and vegetable peeling with less waste. Pressure-assisted ohmic sterilization improves food quality, and conductive packaging enables in-pack heating. Non-food uses include waste treatment and desalination. Unlike other methods, ohmic heating scales up easily with uniform heating, though it requires careful control to manage electrode issues. It’s ideal for processing viscous, particulate-rich foods (Alkanan et al., 2021).

Ohmic heating holds significant promise as a technology that enables rapid and uniform thermal processing of food materials. Its effectiveness depends on several key factors, including the electrical conductivity of the food, electric field strength, frequency, residence time, and rate of heat generation. As a thermal method, it is well-suited for food preservation and stabilization, and it also serves as a valuable pre-treatment step to prepare plant tissues for mass transfer operations such as diffusion, dehydration, and extraction.

Recognized as a smart and emerging technology, ohmic heating has a wide range of current and potential applications. However, extensive research is still needed to fully understand the post-treatment effects. Future studies should focus on changes in flow dynamics, electrical behavior, and key food properties like conductivity, rheology, and particle size.

Economic analyses are also essential to assess the overall feasibility and cost-effectiveness of industrial-scale implementation. Deeper insights into the effects of electric fields on mass transfer, process modeling and design, electroporation and permeabilization phenomena, and the prediction of cold spots and heating patterns in complex food systems will be vital for commercial adoption.

Overall, ohmic heating has the potential to become a core technology in modern food processing.

References

Astráin-Redín, L., Ospina, S., Cebrián, G. et al. Ohmic Heating Technology for Food Applications, From Ohmic Systems to Moderate Electric Fields and Pulsed Electric Fields. Food Eng Rev 16, 225–251 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12393-024-09368-4

Alkanan, Z. T., Altemimi, A. B., Al-Hilphy, A. R. S., Watson, D. G., & Pratap-Singh, A. (2021). Ohmic Heating in the Food Industry: Developments in Concepts and Applications during 2013–2020. Applied Sciences, 11(6), 2507. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11062507

Gavahian, M., Chaosuan, N., Yusraini, E., & Sastry, S. (2025). Roles of ohmic heating to achieve sustainable development goals in the food industry: From reduced energy consumption and resource optimization to innovative production pathways with reduced carbon footprint. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 159, 104947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2025.104947

Cho, E.-R., & Kang, D.-H. (2022). Intensified inactivation efficacy of pulsed ohmic heating for pathogens in soybean milk due to sodium lactate. Food Control, 137, 108936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108936

Javed, T., Oluwole-ojo, O., Zhang, H. et al. System Design, Modelling, Energy Analysis, and Industrial Applications of Ohmic Heating Technology. Food Bioprocess Technol 18, 2195–2217 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-024-03568-w

Misra, S. (2022). Ohmic Heating: Principles and Applications. In Thermal Food Engineering Operations (pp. 261–299). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119776437.ch10.